Under the bonnet: how safe is the global banking system?

Trevor Hubner, MKC Wealth’s investment manager, looks at what caused Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse to fail, the impact on investment markets and the measures that are in place in various jurisdications to prevent something similar happening again.

The end of the quarter proved to be particularly interesting. Silicon Valley Bank (SBV), the 16th largest bank in the US, collapsed in the space of three days, after announcing a $1.8bn loss on its bond trading operation and a $2.25bn share issuance to meet subsequent cashflow requirements. Investors shunned the share offer, selling shares instead. The share price fell by 60% and, with clients demanding their deposits be returned, the bank collapsed.

A bank failing can have knock-on effects on other banks, as banks tend to lend to each other, creating what is known as counter-party risk. It was reassuring to see the relevant authorities acting quickly and decisively, negating the need for lender banks to sell assets at a loss, thereby calming market uncertainty.

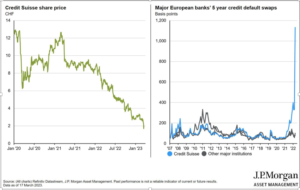

Meanwhile, in Europe, a there was a banking problem of a different magnitude. The problems at Credit Suisse (CS) were already well-known: bad investments, scandals and poor management over the previous two years had created a certain amount of negative feeling about the bank. The graphs below demonstrate how the market had lost faith in the bank between January 20 and January 23. The one on the left shows how Credit Swiss shares fell during that period. The one on the right shows the cost of insuring against the bank defaulting compared to its peers over the same period.

As you may know, Credit Suisse was bought by UBS for CHF3bn in March, with the Swiss National Bank (SNB) guaranteeing an additional CHF9bn in short-term losses. As bond investors the deal initially caused us some concern. There is a hierarchy as to who gets money back when a bank or company fails: bond-holders get money before shareholders. But the Swiss National Bank used a technicality to do otherwise and some bond holders got nothing, while shareholders got a small amount back. The bond-holders concerned held a specific type of bond, but this set an unwelcome precedent and had a negative impact across all bonds issued by banks. Investors and fund managers, including ourselves, were therefore reassured when the Federal Reserve, Bank of England and the European Central Bank all criticised the decision to “zero” these bonds and reaffirmed that banks in their jurisdictions would not be allowed to take this course of action. Time will tell what reputational damage this has done to the Swiss banking system.

Although the issues with Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse attracted a lot of headlines, the situation was very different to that in 2008/9. Stricter measures are now in place (Basel III) to ensure that banks hold more in cash and liquid assets, the aim being that they will always be able to meet their cashflow requirements. This “buffer” of liquid assets has been stress-tested over the past decade and authorities are confident that it is sufficient to prevent a collapse of the system. While and European banks have stuck rigorously to these rules, some US banks, including Silicon Valley Bank, successfully applied for exemptions which allowed them to hold less cash and more in assets.

As its name suggests, Silicon Valley Bank mainly catered for tech firms in California, which deposited the considerable cash they accumulated during the pandemic with it. When interest rates rose sharply the value of the bonds Silicon Valley Bank held against these deposits fell. At the same time, the tech companies’ profits dropped so they wanted their money back, forcing Silicon Valley Bank to sell assets at a loss which caused its collapse.

While there is still some nervousness within the banking sector and share prices remain lower than they might otherwise be, most analysts are confident that the tighter regulation will do its job. As always there is the potential for unknowns and problems at a core bank would certainly result in investors selling and share prices falling.

4 April 2023

Important Information

The material in this article is for information only. The article is for UK residents only. It is the property of MKC Wealth Limited and should not be distributed without prior permission from this business. The information contained in this article is based on our interpretation of HMRC legislation which is subject to change. The value of your investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and neither is guaranteed. Changes in exchange rates may have an adverse effect on the value of an investment. Changes in interest rates may also impact the value of fixed income investments. The value of your investment may be impacted if the issuers of underlying fixed income holdings default, or market perceptions of their credit risk change. There are additional risks associated with investments in emerging or developing markets. Investors could get back less capital than they invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. MKC Wealth Ltd does not provide taxation advice. Taxation advice is not regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.